The article discusses the recent focus on celestial tails, particularly relating to the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, which developed both a tail and an unusual anti-tail during its journey through the solar system. While comets are commonly known for their tails, the article reveals that Earth also has a tail extending at least 2 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) into space.

Mercury, which has a thin atmosphere, possesses a sodium tail—a bright orange glow caused by sunlight scattering and radiation pressure. This phenomenon allows observers on Mercury’s night side to see this tail at certain times of the year.

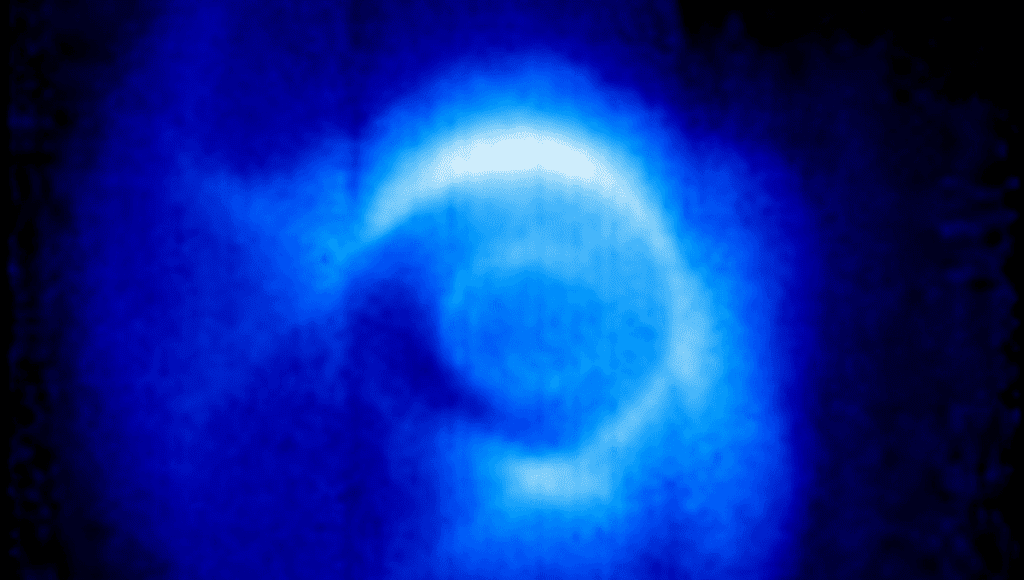

Earth’s tail, known as the “magnetic tail,” is less visible but follows Earth into space, largely shaped by its magnetic field, or magnetosphere. This field protects Earth from solar wind and traps plasma, creating a tail-like structure when the solar wind distorts the magnetosphere. The article explains this using an analogy of a raindrop’s shape changing as it falls. The tail is a permanent feature that fluctuates with solar activity, such as when coronal mass ejections alter its structure.

Despite previous exploration by various spacecraft, much about Earth’s magnetic tail remains a mystery due to its vast size. The European Space Agency emphasizes the ongoing challenges in studying this extensive region, which stretches far beyond the capabilities of a single spacecraft.

Source link